Warning: This post contains images that may be disturbing.

Witnesses claimed that only 2 weeks before the fire, the famous Parisian psychic Madame Henriette Couedon entered a trance and ominously foresaw “near the Champs Elysées, I see a place not high, for it is not for pity.. but for the purpose of charity. I see the fire rising and the people screaming. Grilled flesh, charred bodies..”

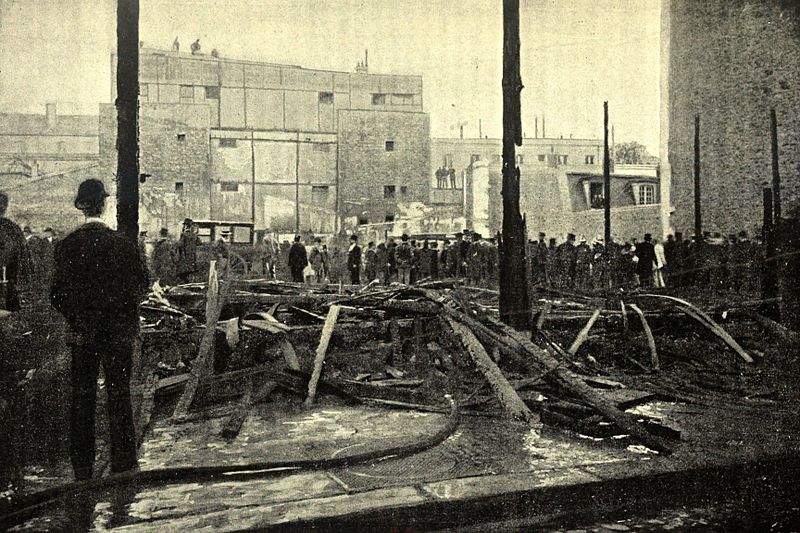

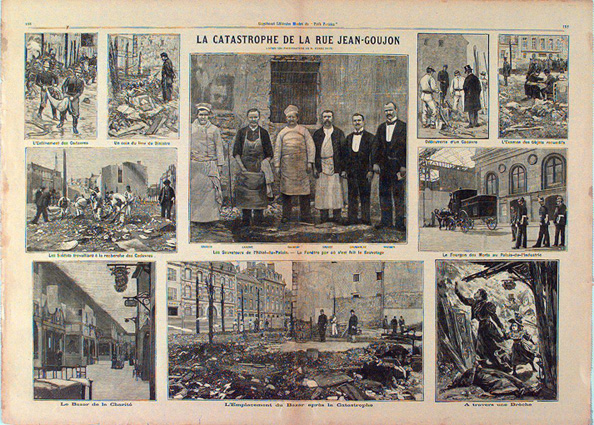

In the hours after 17h30 on May 4th 1897, a 2nd wave of horrors emerged from the smoking ashes where only one hour prior the annual Bazaar de la Charité had stood. The injured that were well off were discreetly taken home where they had private doctors and nurses to care for their wounds. The nearby Palais de l’Industry (today the site of the Petit and Grand Palais) became a makeshift morgue, where the husbands and fathers were sent when they couldn’t find their wives, daughters, and children at the nearby hospital. There they were forced to attempt to identify their loved ones, most of which were burned beyond recognition.

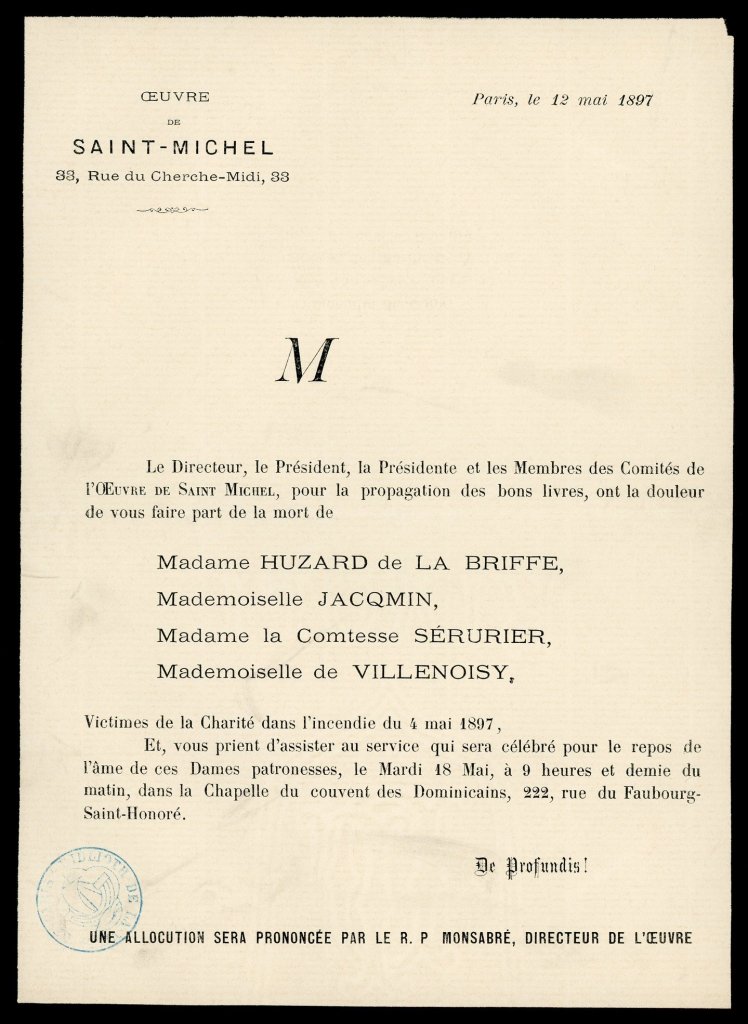

The corpses once known by their respectable titles such as Countess d’Hunolstein, Marquise Maison, and Baroness Laumont were now distinguished by what little remained of them. One maid was able to find her mistress by the charred remains of a petticoat and the stitching she recognized as her own. Others were claimed by their jewelry and marriage rings. In one of the first cases of forensic dentistry, the Duchess of Alencon was identified by her gold fillings. As many as 30 corpses were simply beyond any recognition.

Back at the site of the fire, a more gruesome task was being completed of which war veteran George Grison, who witnessed the horrors of 1870- declared to have never seen anything so grisly. Many of the victims had succumbed not to the flames, but to being trampled upon. The fire burned so savagely that body parts were unidentifiable. The press went wild and narrated the disaster down to the most macabre details, describing the charred and nude bodies of former female social and religious elite with disturbingly intimate details.

Combined with PTSD and disfigurement of many survivors, this created a cloud of shame over the fire that led to its memory being repressed by polite society. Gentlemen who lost their female family members, some their wives, mothers, and daughters all at once- retreated to their country homes and mourned privately away from society.Burn victims recovered at home, then hid with their scars for the rest of their lives. The lucky ones who escaped unharmed often never spoke of it again, and its only thanks to the popularity of genealogy tracking that many current descendants are discovering they had ancestors who perished here- the living preferred to keep those horrors in the past.

The press also focused on the controversies around the fire as a battle of the sexes and social discrimination. They implied that the reason for the disparities between the men and women (118 females and 7 males, including a 4 year old orphan) was because the men savagely sacrificed the women to survive. A New York Times headline on May 16th read “Cowardice of Paris Men Exhibited in Brutal Form During the Burning of the Charity Bazaar”. Today this is considered an exaggeration because so few men were present inside the bazar itself at the time of the fire.

Whatever brutal acts did occur can only be attributed to the animalistic fight to survive. However it was obvious that the real heroes of the fire were the working class, like the stable hands and kitchen workers that saved so many lives. For these reasons, as well as the upcoming horrors of both world wars; that the tragedy of the Bazar de la Charité became largely obscure and unknown.

Post fire, Parisians were in mourning, but they were also mad. Who was to blame? At the memorial service of Notre Dame on May 8th, the priest implied the fire was a consequence of man and their endless pursuit of science, which caused them to provoke the wrath of God. At the trial, the projectionist claimed he had tried to explain the potential dangers with his allotted lack of space, but nothing was done. When one of the organizers later testified, it was said by a witness that when asked if the building was safe, he replied “Of course, smoking will not be allowed inside”.

It was determined that the president of the charity held the most responsibility for negligence, but because he had saved the lives of a few women (although his sister perished) he was let off with a large fine and ruined reputation. Ultimately, the fault was in the structure, which lacked clearly marked exits.

It didn’t help that the tinderbox-like framing held endless potential explosives inside, where everything from the combustible wall drapery to the highly flammable lotions worn in the hair of the women contributed to the fire’s intensity. In addition, a lack of available water prevented the fire fighters from suppressing the flames as fast as they could have. All of these issues brought new legislation to protect the public from fire at large events. Continue to Part Four for more.